How Africa Almost Killed Me (& What It Taught Me About Life)

Anaphylactic shock, Mount Kilimanjaro, and the soldiers of the mountain.

I almost died climbing Mount Kilimanjaro.

I wouldn’t be writing this right now if I hadn’t been saved by 3 friends, a dozen Tanzanian “soldiers of the mountain,” and a little bit of luck.

The story starts with a not-so-serious conversation…

Dreamers That Jump

In February 2022, my friend Joe Lindley and I were talking.

We had both just watched 14 Peaks, a documentary about a Nepal-born mountaineer who summited fourteen 8,000+ meter peaks in under 7 months — a record that beat the previous record by more than 5 years.

Joe and I were inspired by the documentary and craving some adventure.

Joe began doing some research into the Seven Summits — the highest mountains of each of the seven traditional continents:

Africa: Kilimanjaro - 19,341 ft

Europe: Elbrus - 18,519 ft

South America: Aconcagua - 22,828 ft

Oceania / Australia: Carstensz Pyramid - 16,024 ft

North America: Denali - 20,322 ft

Antarctica: Vinson Massif - 16,050 ft

Asia: Everest - 29,029 ft

He learned that while Mount Kilimanjaro was the 4th highest of the Seven Summits, it was generally recommended as the first summit to attempt because it’s fairly accessible and you don’t need technical climbing or mountaineering skills to complete it (neither of which Joe or I possess).

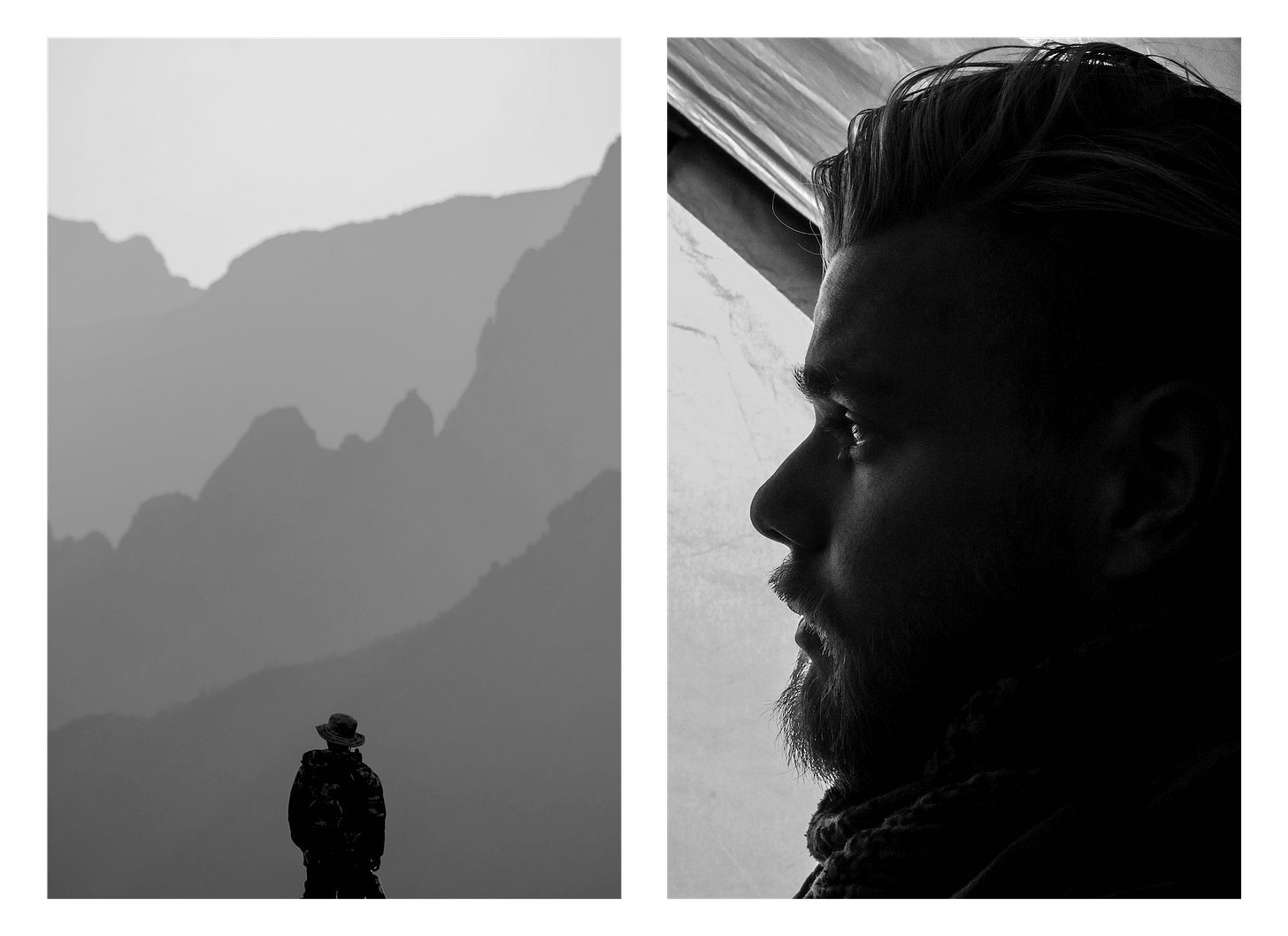

Mt. Kilimanjaro, located in Tanzania, is the largest free-standing mountain in the world, meaning it’s not part of any mountain range.

Because there are no other mountains around it, the relative size of Kilimanjaro is astonishing.

To truly appreciate how huge it is, you have to see it in person, but one of my friends, Pat Campbell, said it best, “It’s one of the biggest things in the world you can look at.”

You can see the summit of Kilimanjaro from the town of Moshi, Tanzania, which is at around 2,300 ft above sea level. From that perspective, you’re looking at something that’s 17,041 feet tall (19341 - 2300 = 17,041)!

There are 2 types of people in this world:

Dreamer

Dreamers that jump

Everybody dreams of having spectacular experiences.

Maybe you want to go see the pyramids in Egypt. Or eat pasta and drink wine while traveling the coast of Italy. Or surf the beautiful beaches of Costa Rica while bathing in the sun.

But most people never take any action to realize their dreams.

“I can’t because X. I shouldn’t because of Y. I can’t afford it. Etc. Etc.”

There’s always an excuse.

But the excuses are usually a front for the real reason — they’re not willing to face fear and uncertainty.

When you do something new and novel, there’s always going to be a layer of fear and uncertainty intertwined with excitement and marvel.

It’s your intelligent body trying to protect you from harm; unknown = dangerous. But it’s also preventing you from experiences that can add substance to your life.

Everybody feels this fear and uncertainty.

The only difference between the first and second types of people is that the second jump. They say “fuck it” and take the plunge towards the unknown.

They may not know exactly how yet, but they commit to doing what they need to do to figure it out.

After that first conversation about Kilimanjaro, Joe and I decided to jump.

We were flying to Tanzania in August, giving ourselves 6 months to prepare.

Discovering Purpose

Shortly after committing to climbing Kilimanjaro, I was talking to my Dad on the phone, telling him about my plans.

He said, “Oh cool, that’s something your grandpa always wanted to do.”

My grandpa, Forrest West II, passed away in 2021.

He had battled Parkinson’s disease for 2 decades, a brain disorder that slowly breaks down the body and causes unintended and uncontrollable movements. It was something difficult for the rest of the family and me to witness.

He was always a very strong, capable man, so seeing him deteriorate into such a vulnerable and fragile state was difficult.

He was a hunter and fisherman and loved the outdoors. Mount Kilimanjaro was right up his alley and would have been something he’d have loved to do.

My Dad then asked me, “What do you think about taking some of your Grandpa’s ashes to the top of Kilimanjaro and spreading them?”

Woah.

An air of seriousness suddenly filled me.

What an honor to be able to take my grandpa’s ashes to a place he always wanted to go but never got the opportunity to. I told my Dad, “Of course, I’ll bring Grandpa to Kilimanjaro,” and just like that, the trip had a powerful added purpose.

But what was the purpose of doing this in the first place?

Why did I feel compelled to climb this mountain in Africa?

It’s a question I asked myself a lot while preparing for the trip.

I don’t really have any aspirations to become a mountaineer, and I don’t particularly enjoy hiking, or as I like to call it, “walking without a purpose.”

The more I pondered, the more I realized there wasn’t just one reason; there were many.

The first reason was my ego. A part of me wanted to be able to say, “I climbed the tallest mountain in Africa.”

Can you blame me?

The second reason is I’ve experienced enough type 2 fun to know the value.

Type 1 fun is pleasant while it’s happening. Surfing, snowboarding, and beers with your friends are all examples of Type 1 fun.

Type 2 fun is miserable while it’s happening, but when it’s over, and you reflect on it, you remember it as fun and would do it again. Conditioning during soccer practice, hiking in freezing cold weather, and running a marathon are all examples of Type 2 fun. Type 2 fun is more gratifying and memorable than Type 1 fun, which is why people seek it out.

Climbing Kilimanjaro is definitely Type 2 fun.

The third reason was for the adventure.

Kilimanjaro is in Africa, a wild and expansive place dramatically different from what I’m familiar with here in the US. There’s an excitement and mystery associated with a place like Africa, so traveling there for the first time was a large part of the draw.

The fourth reason was for the personal growth I knew would come as a result of stepping outside of what I was comfortable doing.

Jordan Peterson says, “You should be better than you are, but not because you’re worse than other people; it’s because you’re not everything you should be.”

I feel incredibly lucky to be given the gift of life, and so I’m driven to make the most of it.

We’re all dealt a different set of cards, but by focusing on continually raising the bar on what it means to be the best version of you, I believe you maximize the good you’re able to receive from life.

The Mint Boys

We had around 10 people that were interested in the trip, but only 4 jumpers — Joe, Pat, Weston, and me, aka The Mint Boys (a nickname we gave ourselves because of the color of our matching shoes).

I couldn’t have asked for a better group of men to go on a trip like this with.

Pat Campbell is a creative genius. He has a unique way of viewing the world and is able to see beauty and art in everything. He brings an infectious, light-hearted, and positive energy to any group he’s around. Pat’s laugh is contagious, which means you’ll be laughing a lot when you’re around him. Pat took most of the photos in this article, including the feature image.

Joe Lindley is one of the most optimistic, “glass half full” guys you’ll ever meet. He brings an energy that uplifts everyone he’s around. He’s also very philosophical and is able to find meaning in the seemingly mundane and common. Joe’s a visionary and inspires the people he’s around to see the world he sees.

Weston Miller might be the nicest, most conscientious person I know. He’s also one of the strongest. You’ll never hear him complain or show signs of weakness, even though he’s in constant chronic pain due to an autoimmune disease. Rather than play the victim or feel sorry for himself, Weston lives life with discipline and a positive attitude. He’s truly an inspiring person to be around.

With the crew set, it was time to start preparing to climb to the “roof of Africa.”

The Preparation

I felt like a UFC fighter in training camp preparing for Kilimanjaro.

For the 6 or so months leading up to the trip, I took my health and fitness extremely seriously.

My diet was on point, and I didn’t drink any alcohol (except the weekend I got engaged to my lovely fiancé, Erin).

There’s some research that shows that training in the heat can improve your performance at altitude, so many of my workouts were done in the 100+ degree Austin summer heat.

I put on 15 pounds and have never felt better physically.

However, knowing what I know now, I didn’t need to be as disciplined as I was with my training.

Don’t get me wrong, you have to be in good shape to climb Kilimanjaro.

You’re hiking for 4-12 hours each day, which sounds like a lot, but all it is is walking.

The real challenge of Kilimanjaro and the part that the rest of the group and I underestimated was doing all that walking while you’re sick.

If you’re climbing Kilimanjaro, it’s not a matter of “if,” it’s a matter of “how bad” you’ll experience Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS).

AMS feels like you have the flu.

Typical symptoms include:

A pounding headache and dizziness

Nausea and vomiting

Chills and an aching body

Fatigue

Difficulty sleeping

Loss of coordination

Loss of appetite

Climbing Kilimanjaro is more of a mental challenge in staying positive than it is physical because of how miserable hiking for hours at a time with AMS is.

The only way to mitigate the effects of AMS climbing Kilimanjaro would be to spend time at altitude before your trip.

If you live in Denver at 5,000 feet, you’ll be in better shape than if you live in Austin (like me) at 489 feet.

In addition to the physical preparation, there’s a decent amount of gear required to ensure you safely summit. I spent about a month before the trip accumulating everything I needed to climb the mountain, then double and triple checking I had everything.

August rolled around quickly, and I was ready.

The Trip

Before we knew it, The Mint Boys were on a plane to Tanzania.

Day 1 - 2: Travel

Getting to Tanzania is no easy feat.

We drove from Austin to Houston, flew from Houston to Doha, and then took a flight from Doha to Kilimanjaro International Airport (KIA) — 29 hours of total travel.

On the flight to KIA, we saw Mount Kilimanjaro for the first time on the plane.

It was breathtaking.

You could feel the energy on the plane rise as everyone started seeing it from the windows.

Once we landed, I walked off the plane and consciously felt my feet touch African ground for the first time.

We made it.

We’re in Africa.

Day 3: Moshi, Tanzania

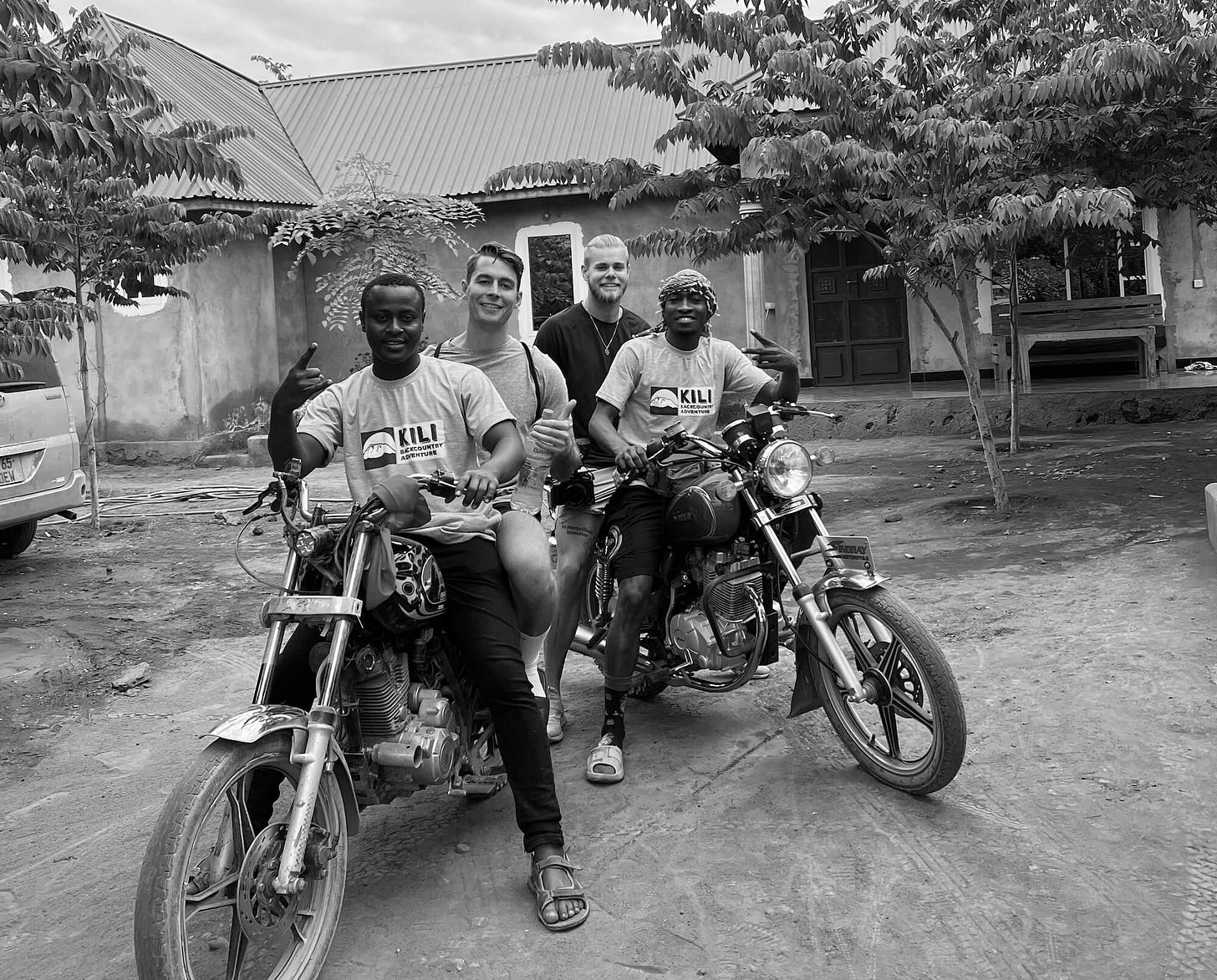

We, The Mint Boys, were picked up at the airport by two guys; Hamad and Chuku.

Hamad is an incredible guy who you will hear more about later in the story. He’s the younger brother of Abdul, the owner of the guide company we used, Kilimanjaro Backcountry Adventure.

When you climb Kilimanjaro, you do it with a team of people.

You have a guide, assistant guide, specialty porters, and regular porters.

Chuku was the chef (a specialty porter) but preferred to be referred to as “stomach engineer.” Chuku’s smile and energy were infectious from the moment he picked us up, which put us all in a buzzing mood.

Hamad and Chuku took us to our hotel in Moshi, where we spent the night before starting our ascent. Our hotel had a rooftop area 6 floors high where you could sit and look out into the city.

Moshi is lush, green, and beautiful, with Mount Kilimanjaro bordering the Northern side.

From our perch on the roof deck, rusty metal roofs and run-down old buildings made up the majority of the city. Chinese-manufactured motorbikes and 3-wheeled auto rickshaws, the most common form of transportation in Moshi, were buzzing through the streets.

Goats and cattle were wandering on the side of the road, no apparent owner in sight. Men and women walked down the street carrying huge bags full of rice and other agricultural crops on their heads.

It felt like we were on another planet, yet familiar at the same time.

We met with Abdul in the early afternoon to go over the Kilimanjaro climbing principles and run through a gear check.

The 6 climbing principles are meant to keep you safe on the mountain and are as follows:

Be positive: Kilimanjaro is a marathon, not a sprint. Optimism is crucial to get through 8 days on the mountain and AMS.

Pole Pole: This means “slowly slowly” in Swahili, the most common language in Tanzania. If you try to climb too fast, you risk worsening your AMS symptoms, so the name of the game is to take it slow.

Drink lots of water: 4-7 liters a day, to be exact. If you get dehydrated, your AMS symptoms will be much worse, and you can put your health at risk at higher altitudes.

Eat lots of food: AMS makes you lose your appetite, so eating becomes difficult on the mountain. You’re hiking for many hours each day and burning lots of energy, so refueling is key in keeping your energy level up.

Bring the right gear: The temperature at the base of the mountain can be in the 80s, but temperatures at the summit can get below 0. The right gear is crucial to protecting yourself from the cold and the sun at high elevations.

Listen to your guide: Kilimanjaro Backcountry Adventure guides have summitted Kilimanjaro hundreds of times. They have years of experience, so when they tell you to do something, it’s in your best interest to listen.

All our gear looked good, so we said our goodbyes to Abdul, ate dinner, and then went to bed.

Day 4: Hiking Through the Rainforest

We woke up, packed our bags, ate breakfast, and then were picked up by a bus to drive to the base of the mountain.

On our way, we saw a group of giraffes eating leaves off of trees.

Everything felt so foreign and unfamiliar. I sat quietly most of the bus ride in a trance, taking it all in.

When we got to the base of the mountain, our guides began handling the paperwork we needed before we could legally start our journey, so we ate a quick lunch and then waited in anticipation.

After a couple of hours, we finally began our ascent.

Kilimanjaro is made up of five major ecological climate zones:

Cultivation Zone: 2,600 to 6,000 feet

Rainforest Zone: 6,000 to 9,000 feet

Heather and Moorland Zone: 9,000 to 13,000 feet

Alpine Desert Zone: 13,000 to 16,000 feet

Arctic Zone: 16,000 to 19,341 feet

You drive through the Cultivation Zone and then start the climb in the Rainforest Zone.

The rainforest is gorgeous.

It’s wet, green, and dense, with trees, plants, vines, and shrubs that look like they’re straight from Pandora (the planet the movie Avatar is set on).

We saw Blue and Colobus monkeys relaxing in the trees after they had finished their midday feasts.

After a 3-4 hour hike, we reached Mti Mkubwa Camp, located at 9,120 feet.

Our camp was already set up by the time we arrived.

The porters hike 3x as fast as us while also carrying ~4x the weight. While our only job is hiking, the porters all have jobs when the hike is finished. There’s a chef, waiter, people that set up the tents, a guy who carries and sets up the toilet, porters that go fetch water, etc. They’re impressive, durable, and amazing people.

After we got cleaned up after the hike (i.e. changing our clothes and wiping down with baby wipes), we went to the meal tent for dinner.

We were all exhausted from jet lag and hiking, but Joe took the cake.

He was so tired that instead of pouring hot water into his mug to make hot chocolate, he poured the hot water directly into the container that held all the hot chocolate.

We went to bed that night and slept well. We didn’t know this at the time, but it would be our last good night of sleep.

Day 5: The Heather and Mooreland Zone

I really enjoyed our morning routine on the mountain.

First, a porter named Moody is your alarm clock. Moody is awesome. He’d say, “Hello, helloooo. Tea or coffee?” And then serve you tea or coffee in your tent.

After giving you 15 minutes to wake up, it was time for “wash wash.” A bucket of warm water was placed outside of your tent, and you’d splash your head and face with the water to clean off.

After “wash wash,” you got dressed and pack up all your gear before heading off to breakfast.

All the meals were extremely carb heavy. I’m not sure if this is by design, but it’s delicious at the low elevations and horrible at the higher elevation when you don’t have an appetite.

We were served porridge, bread, french toast, a Tanzanian-style pancake, fruit, one egg, and a beef sausage link very similar to a hot dog.

After breakfast, our camp was packed up by the porters, and then we continued our trek.

We climbed from Mti Mkubwa Camp to Shira 1 Camp, which is at 11,500 feet.

During the 6-hour hike, we left the Rainforest Zone and entered the Heather and Moorland Zone.

The change in ecological climate zones is visually obvious.

All of a sudden, the tall trees, vines, and dense vegetation became shorter trees, shrubs, and grasses.

The Mint Boys were in high spirits as we got to Shira 1 Camp.

We cleaned up, ate dinner, and then went to bed.

Day 6: Shira Cathedral

We awoke with our sights set on summiting Shira Cathedral at 12,779 feet.

Mt Kilimanjaro is a stratovolcano made up of three cones: Shira, Mawenzi, and the highest, Kibo. Shira Cathedral is the summit of Shira.

The day was long, but we got to Shira Cathedral without any hiccups.

At this point, we’re well above the clouds.

The view was spectacular.

We hike from Shira Cathedral to Shira 2 Camp, and that night, we are rewarded with one of the most gorgeous sunsets I’ve ever seen.

After dinner, we’re all tired and turn in early for the night.

Day 7: Acute Mountain Sickness

We all woke up after a poor night of sleep and began feeling the effects of Acute Mountain Sickness — slight headaches, nausea, fatigue, etc.

The plan was to hike from Shira 2 Camp to Lava Tower, a volcanic rock tower that was formed by volcanic activity hundreds of thousands of years ago.

When you’re climbing Kilimanjaro, you complete acclimatization hikes.

The idea is to expose your body to higher altitudes for short periods of time before hiking back down to an altitude your body is more comfortable with so it can adjust.

The Lava Tower hike is an acclimatization hike that takes 5-6 hours and gets you up to 15,333 feet.

The last hour of the hike felt like a dream.

You’re climbing through the Alpine Desert Zone, which is barren but strangely beautiful, with volcanic rock littering the landscape.

At 15,000 feet, you’re working with 44% less oxygen, so your brain is moving much slower than normal, and your body feels heavy and lethargic.

The last 500 feet was a slog, but we made it to Lava Tower and then sat down to have lunch.

Weston takes one bite out of an apple and then immediately starts vomiting from Acute Mountain Sickness.

We all had headaches but were able to relax at Lava Tower for ~45 minutes before starting our descent to Barranco Camp (situated at 13,044 feet).

During the 3-hour descent to Barranco Camp is when we all started really feeling the effects of Acute Mountain Sickness.

Joe had been filming during the ascent to Lava Tower, so he was doing a lot of zig-zagging and walking up and down to get various camera angles. On the descent, he said he had flu-like symptoms, including chills, body aches, and a pounding headache.

Luckily, Weston felt better after vomiting at the top of Lava Tower, but Pat and I both had throbbing headaches that were progressively getting worse.

When we reached Barranco Camp, Weston vomited again, and Joe, Pat, and I hurried to our tents to nurse our pounding heads. No one wanted to eat that night, but we were forced to (Principle 4: Eat Lots of Food).

That night, I slept horribly.

My body ached like I had a fever and my headache kept me awake.

Day 8: The Day I Almost Died

The 5th day on the mountain is a day I’ll never forget.

It’s the day I almost died.

Moody woke us all up, “Hello, helloooooo.”

We were all really struggling.

Ear-splitting headaches, nausea, and body aches. No one wanted to get out of bed.

After slamming some Advil and eating a light breakfast, we all felt slightly better.

That morning after packing up camp, we had a dance party.

The guides and porters all gathered into a circle and began singing Tanzanian songs and dancing.

There’s a song where they call someone’s name, and that person goes into the middle of the circle for a solo-freestyle dance.

Joe, Pat, Weston, and I were all called into the center of the circle and showed the guides and porters our sweet dance moves.

Even though we felt pretty horrible, the singing and dancing lifted our spirits.

That day, the plan was to climb the Great Barranco wall, past Kissing Rock, and then camp at Karanga Camp.

Right before we started the hike, my stomach grumbled, and I had my first bout of diarrhea — another symptom of AMS.

After relieving myself, we started ascending the Great Barranco wall, a steep, 900-foot cliff face. You put your trekking poles away because you’re now climbing, not hiking. You’re lifting yourself up and over rocks and literally climbing upward.

As we’re ascending, every 20 or so minutes, nature calls.

If you’re wondering, which I know you are, no, there aren’t any bathrooms.

I’m having to find a nice rock or tree to go behind, squat down, and do my business.

Type-2 fun…

We make it to Kissing Rock, a portion of the Great Barranco wall that requires you to flatten, facing the wall to avoid falling off a steep drop. As you shimmy across, you kiss the rock in front of you.

I gave the rock a big smooch and then went to go find a nice rock… again.

There’s a rule the guides have on the mountain that if you have diarrhea more than 4 times in 8 hours, you should consider taking a bacterial antibiotic.

I was beyond that threshold, so I decided to take the antibiotic.

Within 2 minutes of taking the pill, my feet suddenly got itchy.

This wasn’t your average itch.

It was intense, almost painful. I immediately sit down and frantically pull my boots off to itch my feet.

Then my hands get itchy.

Then my body.

At this point, I know something’s wrong.

A thought passes through my mind — “Am I having an allergic reaction?”

I know I’m allergic to sulfa drugs.

“Was that pill I just took for diarrhea a sulfa drug? Shit.”

I quickly tell Joe, Pat, and Weston I have 2 epi-pens in my backpack that I brought… for BEE STINGS, not antibiotics.

It’s worth pausing here in the story to highlight how damn lucky I was to have epi-pens.

I’ve never had a severe allergic reaction in my life.

I went to an allergist a few years ago for “cedar fever,” a term used to describe the flu-like symptoms many people who live in Austin experience when the cedar trees are pollinating.

Towards the end of my visit, the allergist asked me how my body reacts to bee stings. I told him the area around the sting has progressively gotten more swollen each time I’ve been stung, so he recommended that I keep epi-pens around because it’s possible I could develop a more severe reaction over time.

That was years ago, and the epi-pens I had been prescribed were long expired. Right before I left for Africa, a thought crossed my mind that literally saved my life.

“I should get new epi-pens, just in case I get stung by a bee on the mountain.”

Okay, back to the story.

Things start getting progressively worse, and I’m vocalizing the symptoms I’m experiencing.

“I’m really itchy.”

“I see stars and am dizzy.”

“I can’t see anything anymore.”

“I feel like I’m fainting…”

My head slumps forward.

I’m unconscious.

Joe, Pat, and Weston are shocked. A few minutes ago, I was fine, and now I’m completely unresponsive. My breathing becomes labored, and it looks like I’m choking on my swollen tongue.

Joe shoves a pen down my throat to hold my tongue down to help me breathe.

Pat and Weston start digging through my backpack for the epi-pens. They find one and hand it to Joe.

Joe pulls down my pants, exposing my thigh, and then slams the epi-pen into the flesh of my leg.

While this is all happening, Jonas, our lead guide, is screaming for help from the porters above us on the Great Barranco wall. All the porters drop what they’re carrying and begin sprinting down to our position on the wall.

After the first epi-pen, my breathing improved, but I was still unconscious. Joe, Pat, and Weston start discussing whether or not they should give me the second shot of epinephrine.

A few weeks prior, Pat heard a story at work about a guy's experience with anaphylactic shock after being stung by a bee, so he quickly explains what he remembered.

“They stuck the guy having the allergic reaction with two epi-pens and then rushed him to the hospital.”

They weren’t going to be able to rush me to a hospital, but they did decide to plunge another epi-pen into my thigh.

After the second shot, I regain a loose state of consciousness.

There’s an oxygen mask on my face, and I hear the lead guide, Jonas, yelling my name.

“Cody! Cody, can you hear me?”

I nod but still can’t see anything. My vision is blurry, and I’m tired. So tired.

I drift in and out of consciousness until I suddenly feel I’m hoisted into the air.

A group of porters start carrying me down the Great Barranco wall.

I’m still barely conscious, but from what Joe, Weston, and Pat told me, it was a sight to see.

Four porters are carrying each limb of my body and sprinting down a steep rock face. As one porter slips, another catches me as they continue down at an incredible speed. At one point, I remember being on someone’s back, holding on for dear life.

We make it down the Great Barranco wall, and then I’m loaded onto a stretcher and carried across a valley to Barranco camp.

When we get to Barranco camp, Joe starts running around, asking the other climbers if they have medicine for an allergic reaction.

By some miracle, one of the other climbers has an oral corticosteroid that she gives Joe.

Joe pops one of those puppies in my mouth, and then shortly after, I regain a steady state of consciousness.

My vision is back.

Whew.

While I’m trying to make sense of what the hell just happened to me, Joe, Pat, Weston, and our guides are working on an evacuation plan to get me off the mountain and to a hospital.

In a typical emergency situation on Kilimanjaro, the Kilimanjaro National Park helicopter would pick me up and take me to a hospital.

But the helicopter is broken.

Murphy’s law — what can go wrong, will go wrong.

Jonas gets a private helicopter company from Nairobi on the phone, and they agree to come to evacuate me off the mountain.

We’re told the helicopter would be there in 3 hours.

While we waited, the event began to set in for all of us.

We were all really emotional.

Traumatized by the event but also so grateful I was recovering.

Below is a picture taken while we were waiting for the helicopter — Weston is on my right and Pat's on my left.

We find out that only one person would be able to ride in the helicopter with me, so Joe volunteers.

We all talk and decided as a group that Pat and Weston needed to finish the climb to Kilimanjaro’s summit.

As much as they didn’t want to split off from Joe and me, we all knew they needed to keep going. Not just for themselves but also for me, Joe, and my grandpa.

We all felt a shared responsibility in getting my grandpa’s ashes to Kilimanjaro’s summit, so I passed the torch to Pat and Weston.

Grandpa's ashes were now in their hands, literally.

We all said our emotional goodbyes, and then Pat and Weston began climbing the Great Barranco wall… for the second time.

3 hours turn into 4.

4 hours turn into 6.

Still no helicopter.

The sun is going down, and we are forced to face the reality of the situation we’re in — the helicopter is not coming.

We have two choices:

Stay at Barranco Camp overnight and try to get me evacuated in the morning, or

Hike 8 hours down the mountain’s most difficult and treacherous trail

Jonas ultimately decides he wants to get me out of the elevation because it’s definitely not helping me recover. My hands, feet, and face are all very swollen.

We start the descent down the mountain at around 7 pm, right at dusk.

I’m being carried by 6 porters on a stretcher down a steep, rocky path.

Every 2 minutes or so, the porters have to rest me on a rock while they shuffle around and maneuver the stretcher and themselves down the trail.

No more than 15 minutes after we start, I’m set down again.

I hear a discussion ensue, so I yell to Joe, “what’s going on?”

He told me the porters are having issues moving down the mountain with the stretcher and are trying to figure out what to do.

I sigh.

I know we’re not going to get down the mountain if I’m being carried on a stretcher. It’s just too treacherous, so I say, “Screw it, I’ll walk.”

Jonas and Joe shoot looks of disbelief at me. “You sure?”

I was sure.

I have my arms wrapped around two porters, one on each side, and we begin walking down the mountain.

It’s the most brutal and unforgiving terrain we’d faced up to that point in the trip.

After 5 hours of slogging it down the mountain, we reach a camp in the rainforest.

We have no tents or sleeping bags and have just run out of water.

We need to keep moving.

It starts pouring rain in the rainforest, so we’re not really walking down the mountain anymore — we’re sliding down.

Joe is so exhausted from the events of the day and the hike down the mountain that every time we stop for a break, he immediately falls asleep.

It was towards the end of this brutal hike down the mountain that I first heard the porters describe themselves as “soldiers of the mountain.”

I thanked one of the porters helping me down the mountain and commented on how strong he and his kakas (brother in Swahili) were.

He said, “this is our job — we’re soldiers of the mountain.”

Woah.

That short sentence gave me incredible insight into who these men were.

They hike Kilimanjaro sometimes twice a month while carrying the gear that makes the trek more comfortable for climbers like Joe, Pat, Weston, and I. When there's an emergency situation like the one we all experienced, they’re the ones responsible for remedying the situation.

Climbing Kilimanjaro is also how they support their families.

They are truly “soldiers of the mountain.”

At around 3 am, we see a truck on the trail in front of us.

I have tears in my eyes. We made it, holy shit, we made it.

We’re driven back to Moshi, and once we arrive back in the city, I’m asked if I want to go to the hospital.

At this point, I’ve started to feel better, and all I want is a warm bed. I tell them to just take me to a hotel so I can get some sleep, and I’ll figure out what I want to do in the morning.

A Nasty Rash

Joe and I don’t get to bed until around 4:30 am, so we sleep the entire morning.

We lounged around for a couple hours in the afternoon and then I call Erin. I give her the details of everything that had happened the previous day. It was an emotional conversation.

Next, I’m on the phone with my Mom giving her the download.

10 minutes into the conversation, I look down and notice a rash on my leg. I lift up my shirt, and my jaw drops to the floor.

I have the most disgusting rash I have ever seen!

I quickly tell my Mom I need to go and figure out what to do about the rash.

Joe texts Abdul and asks for him to get us a ride to a hospital.

Hamad, Abdul’s brother, quickly shows up at the hotel to pick us up.

Later, I found out Hamad had left a wedding to pick us up. What a selfless, amazing guy. Thank you, Hamad.

When we arrive at the hospital, I’m stunned.

Everyone is dressed in normal clothes and is laughing and joking around. It does not look like a medical establishment which immediately puts me on edge.

I’m quickly brought into a room where I speak to someone who I believe was a doctor.

I tell him what had happened the previous night and then showed him my rash. He prescribes 4 different medications to me, one of which is an injection of a drug called Succicort, a steroid.

I’m brought back into the lobby, shown the drugs, and then brought into another room for the injection.

The room is dirty and littered with buckets and tubs full of stagnant water. It was like someone forgot to do the dishes.

A guy wearing a zip-up hoodie starts wrapping an elastic band around my lower forearm and, in broken English, tells me he’s going to give me the injection… IN MY HAND.

At this point, I’m the opposite of comfortable. I tell the guy to wait while I call my grandma (who was a nurse) so I can run everything I’m about to be given by her.

She gives me the green light, so I sit back down for the injection.

The hoodie guy missed my vein the first time and so had me hold a cotton ball on the injection site while he tried again.

After successfully finding my vein the second time and injecting the steroid, he gives me another cotton ball and then sends us on our way.

As we’re leaving the hospital, I realized there was no disinfectant used before or after the injection.

We drive to another pharmacy, and I buy a box of 200 alcohol wipes to clean my hand where I received the injections.

Hamad drops us off at the hotel and then goes back to the wedding.

Joe and I are wiped out and are asleep before our heads hit the pillow.

Silver Linings

The next morning, both Joe and I were feeling really low. The past few days had been an emotional whirlwind, and it was catching up to us.

The phone rings — it’s Abdul.

He wants to show us the village where he not only grew up but also currently lives. Joe and I aren’t really feeling up to it, but we decide it’d probably be good for us to get out of the hotel to take our minds off things.

Abdul picks us up in a van, and we start the 45-minute drive to his village. The road is a bumpy, dirt road. It’s so bumpy, in fact, that there’s a name for the sensation you get while in the car — they call it an “African massage.”

Joe and I start commenting on the fact that in Tanzania, they drive on the “wrong side,” and we begin wondering if driving would be any different for us. Abdul immediately pulls the car over and tells one of us to get in the driver's seat. I giddily oblige and drive on the ‘wrong side” for 10 minutes before turning it over to Joe.

Abdul taught us a bunch of interesting things about Tanzania as we drove to the village:

The Baobab tree, also known as “the upside down tree, is the biggest, oldest tree in Africa. It’s called “the upside down tree” because its branches are bare of leaves and look like roots.

There are so many motorbike accidents in Tanzania that certain hospitals have entire wards dedicated to taking care of injuries caused by these accidents.

Most of the motorbikes are Chinese-made, and you can purchase them for around $1k USD.

The Tanzanian population is mainly Christian or Muslim. There are no religious issues, and everyone gets along with everyone for the most part. Christians will marry Muslims, and Muslims will marry Christians, but typically the women will convert their religion to whatever their husband is.

When we arrived at the village, we’re given a tour of Abdul’s house.

It’s a gorgeous home, but the highlight is his lush backyard. It’s covered in green grass, and he has trees, bushes, and flowers planted throughout. You can tell it’s something he’s put a lot of effort into making beautiful.

There are 3 structures that are halfway built in his backyard.

Joe and I ask about them, and he begins telling us the story behind them.

His dream is to have climbers that he’s guiding to the summit of Kilimanjaro stay in his village before and after the Kilimanjaro trek rather than in the hotel in Moshi. He says he’s taking all the extra money he makes from the guide company he owns and is investing it into these buildings.

Joe and I tell him we love the idea.

It would not only be a more peaceful, tranquil stay before the climb because you’re out in the countryside rather than in the city, but it’d also provide travelers with a more authentic Tanzania experience.

After the house tour, two of Abdul’s friends pick us up on motorbikes and give us a tour of the village.

As we ride through the village, groups of children wave at us as we drive by and then chase after us laughing. Farmers carrying bags of rice and lumber on their heads see us zooming by and shoot huge, beaming smiles our way.

Everyone was so… happy.

Seemingly much happier than the average person you walk by on the street here in Austin.

Even though the villagers have very little in terms of possessions, they do have something that most Americans don’t have.

Community.

I asked Abdul what he would do in the evenings after his work day was over. He said his family and a few others would go over to his best friend’s home every night, and they would talk. They’d all tell stories from the day and then, around 10 pm, would head home to go to sleep.

How many American families do you know that prioritize spending time with others beyond their immediate family every night?

No screens or TV, just good conversation.

Having community has been shown time and time again to contribute massively to happiness and well-being.

But in America, we prioritize achievement over community.

Naval Ravikant has one of my favorite quotes, “play stupid games, win stupid prizes.”

We play so many stupid games in the US. Power, status, and fame are things we strive for in the hopes they’ll make us happy.

They won’t.

I learned from the Tanzanian villagers that community is what I should be prioritizing in my life.

Joe and I had extra food from the hike we didn’t eat, so we decided to pass it out to the villagers. We gave out power bars and oatmeal balls that were all a big hit.

Joe also brought a few Hot Wheels cars with the intention of handing them out to kids. We had to be careful passing these out because we only had a few, and we didn’t want to cause a fuss.

We rode through fields of rice paddies and learned about the rice farming process, even getting to see a rice harvesting machine up close and personal. We saw boys playing and doing flips into the river while they worked alongside their father.

When we were dropped back off at Abdul’s house, lunch was ready.

Abdul’s wife made the three of us brown rice and beef, potato strips, avocado, mango, oranges, and a shredded salad. The beef was a combination of different cuts from the animal. The meal was delicious, although Joe and I did our best to pick around the beef stomach.

Our conversation with Abdul was a memorable one. He explained to us his way of living, his goals and aspirations, and what it was like growing up in the village we were in.

After lunch, Abdul brought us to a soccer field that had been built as a result of money that had been donated by a climber Abdul had taken to the summit of Kilimanjaro. He told us she was an older woman who, when she saw Abdul’s village, wanted to help in any way she could.

She and Abdul decided a soccer field would uplift the community, giving kids something to strive for rather than getting caught up in things like drugs and alcohol.

When we got to the field, there was a little girls' team practicing, and Abdul asked us if we wanted to play.

“Of course, we want to play!”

For the next hour, we played soccer at sunset with the villagers.

It was magical.

At one point, Joe and I looked at each other with pure joy in our eyes, and both agreed that we so badly needed this.

My heart was full after seeing how happy and content all these people in the village were.

Their smiles and energy were contagious and made me completely forget about the traumatic event that I had just faced.

Abdul drove us back to Moshi as the sun was setting, and Joe and I thanked him for a day neither one of us will ever forget.

Reunion

Joe and I had received word that Pat and Weston successfully made it to the summit of Kilimanjaro.

We were ecstatic!

Both had to continue the journey up to the summit even after witnessing their friend almost die.

Weston, in particular, had been in excruciating pain from his autoimmune condition most of the trip. The pain made it difficult for him to get out of bed in the morning.

One morning early in the trip, Weston slammed his fist into the ground in frustration after spending more than 10 minutes simply trying to get out of bed. Once his body was warmed up, he’d get mobility back, but the mornings were extremely rough for him.

I’m incredibly proud of Weston for summiting despite the chronic pain he dealt with the entire trip. He’s a true warrior.

Both Pat and Weston had taken the torch (Grandpa’s ashes) from me and successfully spread them at the summit. I’m very grateful for these men and what they did, not just for grandpa and me but also for my Dad and grandma.

Sincerely, thank you, Pat and Weston.

I know my grandpa is looking down, shaking his head in disbelief at the series of events that played out on Kilimanjaro. If I had to guess what he’d say to Pat and Weston after hearing they were the ones to get his ashes to the summit, it’d be, “Good show!”

Joe and I were waiting at the base of the mountain for Pat and Weston to return.

It was an emotional reunion when we first saw each other — watery eyes and big hugs ensued. We couldn’t wait to trade stories of what happened after we split up.

Luckily, we were flying to Zanzibar to spend 3 days on the beach.

We drank beers, ate pizza, and swapped stories from the mountain, the hospital, the village, and on the roof deck of the hotel in Moshi.

What an experience.

Memento Mori

I was sitting in the Kilimanjaro airport on my way home when a feeling of unease suddenly washed over me.

After sitting with it for a moment, I understood where it came from — it was from the realization that I could have died on that mountain, and I wouldn’t have known it was my last moment.

When I fainted and then was brought back to consciousness with the epinephrine, I didn’t know I had been unconscious.

I had slipped unknowingly into blackness and then was brought back to light.

“But what if I never woke up?”

It’s a terrifying thought.

Not because of the finality of death but because of how sudden and unexpected it can be.

You assume you have time to experience all the different stages of life.

Growing up and going to school. Heading off to college. Falling in love. Having kids. Watching your kids grow up and have kids.

Most people imagine they’ll die in old age after living a rich life full of laughter and love.

For most of us, that’s an “acceptable death.”

But death is unpredictable, and life can be fleeting.

Merge left on the freeway at the wrong moment, fall awkwardly on a ski trip and hit your head, or take the wrong medication on Africa’s tallest mountain miles away from a hospital.

You can live hundreds of thousands of hours of life, and then it could be all over in a second.

Sitting with this truth was unnerving for me because I experienced the fragility of life firsthand.

It’s like a wine glass. One fatal mistake, and it’s shattered, with no hope of piecing it back together.

The feeling made me want to sit in a cushioned room for the rest of eternity, avoiding all of life’s dangers.

But then I realized how incredible it is that I've made it as far as I have despite life’s fragility.

A deep sense of gratitude quickly followed.

Gratitude not just for the life I’ve lived, but for what I have.

When I regained consciousness on the mountain and realized the severity of the situation I was in, the first thing I thought about was my fiancé, Erin.

I wanted to see her again. I wanted to hold her again. But even more than that, I didn’t want her to have to face losing me.

The thought brings tears to my eyes.

I remember drifting in and out of consciousness, being carried down the side of a 900-foot wall thinking, “I refuse to die because I won’t do that to Erin. So breathe. Just breathe.”

It’s easy for me to get caught up in the BS of life.

But I’m thankful to Mt. Kilimanjaro and anaphylactic shock for the sobering reminder of what really matters to me.

Viktor Frankl, psychiatrist, philosopher, and survivor of four German concentration camps, wrote a heart-wrenching book titled Man’s Search for Meaning.

In it, he answers one of life’s most pondered existential questions — what is the meaning of life?

Here’s one of my favorite passages from the book:

"I doubt whether a doctor can answer this question in general terms. For the meaning of life differs from man to man, from day to day and from hour to hour. What matters, therefore, is not the meaning of life in general but rather the specific meaning of a person’s life at any given moment. To put the question in general terms would be comparable to the question posed to a chess champion:

“Tell me, Master, what is the best move in the world?” There simply is no such thing as the best or even a good move apart from a particular situation in a game and the particular personality of one’s opponent. The same holds for human existence. One should not search for an abstract meaning of life. Everyone has his own specific vocation or mission in life to carry out a concrete assignment which demands fulfillment.

Therein he cannot be replaced, nor can his life be repeated. Thus, everyone’s task is as unique as is his specific opportunity to implement it. As each situation in life represents a challenge to man and presents a problem for him to solve, the question of the meaning of life may actually be reversed.

Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of life is, but rather he must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible. Thus, logotherapy sees in responsibleness the very essence of human existence."

When I faced death on the mountain, the meaning of life at that moment became obvious to me — get back home safe to Erin, for Erin.

Thankfully, I made it.

What’s Next?

It turns out that the drug I took on the mountain wasn’t a sulfa drug. It was another type of antibiotic I had no idea I was allergic to.

What are the odds?

Despite that, I feel incredibly lucky.

Lucky to have had epi-pens.

Lucky to have had the foresight to tell my friends I had epi-pens before going unconscious.

Lucky to have been given corticosteroids by another climber.

Lucky to have been with such a capable group of men that knew how to react in an emergency situation.

I’m lucky to be alive.

Even though I almost died, I plan to go back to Mt. Kilimanjaro and visit my grandpa’s ashes on the summit.

I want to see my Tanzanian friends again.

I want another challenging, type-2 fun experience.

I want to visit the Great Barranco wall, where I almost met death, and be reminded what it taught me about life.

Thank you, Africa.

Until next time.